Lucrecia Kasilag: OPM for the Culture

- May 22, 2018

- 5 min read

There are a lot of definitions to the “Original Pilipino Music” or “OPM”. However, with a google search, you’ll arrive at this as the first definition: that which is originally referred only to Philippine pop songs.

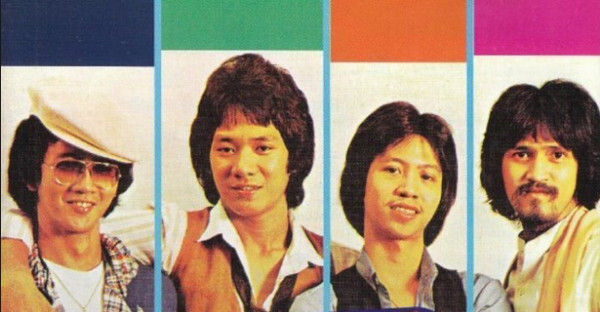

Particularly ballads, these are defined as popular after the collapse of its predecessor: the Manila Sound of the late 1970s. (Rodrigo et al., 2014) This is the generation that had bands like Apo Hiking Society, VST & Co., Boyfriends, Hotdog, Juan de la Cruz Band, and many more that played the music our parents grew up listening or even partying to (Duarte, 2014).

VST & Co. (Left) Boyfriends (Right)

Another interpretation of the term would link “OPM” to the traditional meaning. In a search for original sound, some would refer it specifically to Philippine Gong Music. This type of music involves indigenous roots. Some instruments with such music are the gangsa (Balinese and Javanese Gamelan Music (Adams, 2018) are distantly related to this instrument as well) and kulintang (a modern term for an ancient instrument consisting of a row of small, horizontally laid gongs that function melodically, accompanied by larger, suspended gongs and drums). Different tribes would have their own unique way of playing these instruments, with the most known being the Maguindanaoan and the Maranaw (“Original Pilipino Music”, 2018).

Kulintang (Left) and gangsa (Right)

Approaching “OPM” in a more nationalistic lens, one would say that OPM could well be music of any type composed by a Filipino. Indigenous sounds with a twist like the one in Francis M.’s “Mga Kababayan Ko”, or the mainstream Western sound in “Awitin Mo, Isasayaw Ko” by VST and Co., can thus be considered OPM. Given all these approaches; however, it would seem quite aimless to define Filipino excellence in music by focusing much on the delineation of the genre. Separating the artists in categorizing their mode of demonstrating and expressing the richness of our musical culture and history may come to be counterproductive. OPM should thus be a culmination of all Filipino artists who have created works that show how passionate they are in their field of music, and of course, the love these musicians have for their country and musical heritage.

Lucrecia Kasilag was born on August 31, 1918, La Union. She was an educator, composer, performing artist, administrator, and cultural entrepreneur of national and international caliber; and she has involved herself wholly in sharpening the Filipino audience’s appreciation of music. Kasilag’s pioneering task to discover the Filipino roots through ethnic music and its fusion with Western influences was a motive she had in her compositions, one which other Filipino composers followed on.

She included the indigenous instruments in her orchestral productions. A couple of examples of these works are her prize-winning “Toccata for Percussions and Winds, Divertissement and Concertante” and the scores of the Filiasiana, Misang Filipino, and De Profundis. Kasilag worked closely as music director with colleagues Lucresia Reyes-Urtula, Isabel Santos, Jose Lardizabal and Dr. Leticia P. de Guzman and made the Bayanihan dance Company one of the premier artistic and cultural groups of the country (“Lucrecia Kasilag”, 2018). She was also awarded National Artist for Music in 1989.

The Bayanihan Dance Troupe with Kasilag

One would normally say that her immense knowledge and talent in music were her strong points; but we must not forget that they were due to a passion for discovering Filipino culture down to its roots. This passion laid her innovations in Original Pilipino Music in general. An example of this would be her Folk Songs Series. From 1956-1959, she was able to create her own renditions of famous folk songs from all over. Ti Ayat Ti Maysa Nga Ubing or “Love of a Child”, an Ilocano folk song, Dandansoy, a Visayan folk song or lullaby about a girl who would leave the Dandansoy to go back to her hometown, and even the folk song known to all—Bahay Kubo- are examples of folk songs she arranged. Just to add to how fond she was of creating music for the culture, her works throughout her career did not only involve orchestra instruments, but also consisted of musical scores for different performing arts around the country as well.

An example of this would be the score she made for the ballet Mindanao Myth: Darangan, an epic by the Maranaw. Its first performance took place in the Philippine Women’s University in Davao in 1958. She also scored the opera Jose, Aking Anak, originally by National Artist Leonora Orosa-Gongcuingco. Fellow national artist Rolando Tinio translated it. It was set during the time Rizal was imprisoned and awaiting his execution. It revealed the emotions Rizal’s mother was going through at that time and the similarities between Rizal’s life and that of Jesus Christ (“Leonor Orosa-Gonguingco”, 2018).

The list could go on for Kasilag, also known as Tita King, since her works have reached a whopping amount of 250. Lucrecia Kasilag, incredibly talented, headstrong, intelligent, and having all the resources, chose a career that would further develop the prestige of Filipino music from the roots themselves and incorporate indigenous music. Instead of merely composing for compositions’ sake and participating in the Western scene, she chose to add to the part of the identity in Filipino music that had not yet been explored. She possessed a love for country-being a proud Filipino- that could be likened to that of a hero.

In demonstrating the richness of Filipino heritage and elevating it to world-class standards, she inspired a movement fellow musicians would soon follow through her love of culture. Her goals were indeed the perfect embodiment of Original Pilipino Music; thus, she was able to do all this for the culture.

References:

De La Torre, Visitacion R. Lucrecia R. Kasilag : An Artist for the World. 1985.

Duarte, Angie. "Get Ready for Manila Sound, Then and Now." Philippine American Inquirer, August 23, 2014. Accessed May 17, 2018. http://americaninquirer.net/2014/08/23/get-ready-for-manila-sound-then-and-now/.

“Leonor Orosa-Goquinco” M. Enriquez, accessed May 17, 2018. http://www.orosa.org/leonor_orosa%20bio.htm

“Lucrecia Kasilag” NCCA, accessed May 9, 2018. https://philippines/lucrecia-r-kasilag/

“Original Pilipino Music,” Unknown author, accessed May 7, 2018. https:// theopmmusic.wordpress.com/original-pilipino-music/

Oxford Univesity Press, Oxford. Kasilag, Lucrecia Roces (born 1918). 2001.

“Philippines: Music and Dance” Beth Adams, accessed May 17, 2018. http://world- lyrise.blogspot.com/2017/09/philippines-music-and-dance.html

Tan, Arwin Q. Approaching A Post-Colonial Filipino Identity in the Music of Lucrecia Roces Kasilag. 2016.

Photo of Kasilag taken from: Lucrecia Kasilag: An Artist for the World book by Visitacion R. de la Torre

Photo of the band Boufriends taken from: https://www.discogs.com/artist/1750616-The-Boyfriends-3

Photo of the band VST & Co. taken from: https://www.discogs.com/artist/1849028-VST-Company

Photo of kulintang taken from: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/471822498453636075/

Photo of gangsa taken from: http://ffemagazine.com/musical-instruments-philippines/

Photo of Urtula taken from: http://home.earthlink.net/~chitou/id1.html

Photo of Lardizabal taken from: http://aboutmyrecovery.com/sinulog-festival-and-memories-of-dad/.

Photo of the Bayanihan Dance troupe taken from: Lucrecia Kasilag: An Artist for the World book by Visitacion R. de la Torre

Photo of musical scores taken from: http://www.himig.com.ph/songs/4164-bahay-kubo

http://www.himig.com.ph/songs/335-dandansoy

http://www.himig.com.ph/songs/3315-ti-ayat-ti-maysa-nga-ubing

Comments